Benefits of Pretesting in the Classroom

by Cindy Nebel

(cover image by Mustafa_Fahd on Pixabay)

We have talked extensively about the benefits of retrieval practice on our blog (e.g. here, here, and here). After all, there is more than a century’s worth of research demonstrating its effectiveness for long-term retention (1). The vast majority of this work examines post-testing, providing retrieval opportunities after learning has already occurred. What is far less studied is the idea of pre-testing. While there have been some studies looking at the impact of pre-testing, the results of those studies have been mixed, with some finding promising effects (2), others finding mixed results (3), and some finding very little at all (4).

Recently a new pre-testing study was published, looking at the delayed effects of pre-testing in an authentic classroom (5). That is, this study had less control than some others, meaning that students could engage with material in different ways (more on that later).

In this study, undergraduate students who were enrolled in a large section of a research methods course were given pretests before three lectures during the 10-week course. For each lecture, six concepts were identified that were going to be taught during the lecture. For each of those concepts, 2 questions were written on the topic for a total of 12 questions. The questions were then split randomly into 3 question types:

Image created by Cindy based on methods

So, each pre-test had four items: two identical (that they would see again on the final), one related (whose pair would be on the final), and zero control (both of which would be on the final).

The course instructor waited in another room while a research assistant administered the pre-tests so that the instructor would not be influenced by the items and students were not given the correct answers to the questions.

At the end of the course, students were surveyed about the pre-tests and they took a final exam that included the pretested questions described above – six identical, six related, and six control.

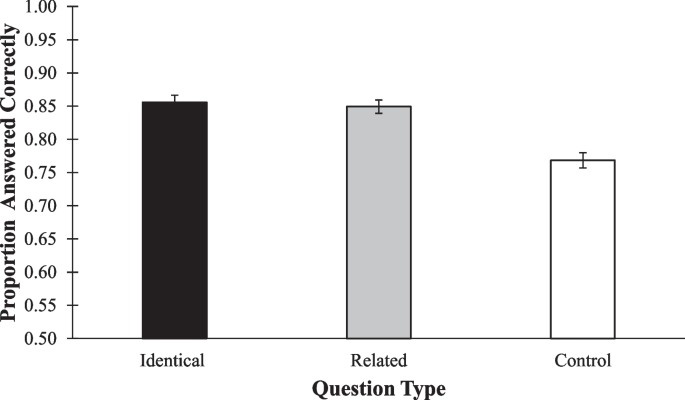

Students did pretty bad on the pre-test, as expected, scoring around 35% on each item type. On the final exam, there was a clear benefit of pre-testing for both the identical and related questions:

Figure taken from cited source

What’s particularly cool about this is that a lot of research on retrieval practice uses identical questions and the research has sometimes been criticized for being primarily rote retrieval as opposed to deeper learning. But this shows a benefit for related material, indicating that there is a benefit for understanding that goes beyond question-answer memorization. And that benefit (in this study) is 10% - a full letter grade.

Students also responded to a survey about the pre-tests. There were some interesting results to the survey.

· Students indicated that they took the pretests pretty seriously even though they weren’t for a grade. Students did have to put their names down in order to connect their scores with their final exam grades, so perhaps that raised the stakes for them a bit.

· On average, students believed they got more than half of the pretest answers correct. This is somewhat surprising. At the time this survey was taken, students have already sat through the lectures and gotten the correct answers, yet they are overestimating how well they did. Still, there was quite a delay between the pretests and this response, so we wouldn’t expect it to be perfectly accurate.

· Students indicated that they used a strategy on the pretest, either a process of elimination or picking an item with familiar terms. This indicates that students had some knowledge before taking the pretest, which allowed them to consider answer choices instead of purely guessing.

· About half of the students indicated that they didn’t think about the (ungraded) pretests after they took them, but the other half reported using the pretests as a kind of study tool. They looked up the answers, studied those items, or talked with their friends about them.

· Interestingly, almost half of the students reported that they engage in some kind of pretesting on their own. They completed quizzes provided by the instructor or those in the textbook before coming to class.

Here’s my take:

There are several possible reasons why pretesting worked in this study.

1) Students paid more attention to the pretested material during the lecture.

2) The pretest activated prior knowledge (some of them are clearly doing a lot of prework), and allowed them to encode the new information more deeply.

3) They were doing a lot of studying of the pretested information outside of class.

4) There are some great spaced retrieval effects going on. That is, students saw the material before lecture, they took a quiz on it during the pretest, then later they reviewed or quizzed themselves on that same material again during self-study.

Of those reasons, three of them depend on students working on their own in a strategic way, outside of class. While there is clearly more research needed in this area to disentangle these possibilities, I feel pretty confident in telling educators that this is a promising technique for certain students. My concern is that these might be the students who need it the least. If they are already doing extra strategic studying that better prepares them for lectures and exams, those aren’t the students I’m worried about. And if this effect requires all that extra work, there’s less that we, as educators, can do about it.

But there are some things. For example, making those pretests worth a very small amount of the total grade and encouraging students to prepare for them could extend this benefit to students who otherwise wouldn’t do that prework. If we provide quizzes in advance of lectures for students to take at home and then provide the pretest questions for students to take home and use as study we might guide them to more effective study strategies. After all, it’ll be difficult for them to practice retrieval if they have to create their own materials.

In short, this data is promising and folks could consider using pretests in their classes. My advice might be to make these pretests a combination of old and new material, retrieval practice and pretest, and to explicitly tell our students how to effectively study for both better scores on pretests and long-term retention.

References:

1) Abbott, E. E. (1909). On the analysis of the factors of recall in the learning process. The Psychological Review: Monograph Supplements, 11, 159-177. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093018

2) Little, J. L., & Bjork, E. L. (2016). Multiple-choice pretesting potentiates learning of related information. Memory & Cognition, 44(7), 1085–1101. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-016-0621-z

3) McDaniel, M. A., Agarwal, P. K., Huelser, B. J., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger III, H. L. (2011). Test-enhanced learning in a middle school science classroom: The effects of quiz frequency and placement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(2), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021782

4) Geller, J., Carpenter, S. K., Lamm, M. H., Rahman, S., Armstrong, P. I., & Coffman, C. R. (2017). Prequestions do not enhance the benefits of retrieval in a STEM classroom. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 2(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-017-0078-z

5) Soderstrom, N. C., & Bjork, E. L. (2023). Pretesting Enhances Learning in the Classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 35(3), 88.