GUEST POST: Podsie - Connecting Teachers and Students to Learning Science

By: Joshua Ling

Josh is a former middle school math teacher and Teach for America alum who believes deeply in the ability of every student to succeed. After getting a master's in Education from Stanford University, he made a career change into software engineering. In addition to building Podsie, Josh also volunteers to teach an AP Computer Science Principles class at a local high school in Oakland, CA. In his free time, he likes hanging out with his wife and their dog Stewie. This past February, Josh and his co-founder had the privilege of joining Megan on The Learning Scientists podcast to chat about Podsie.

If you’re interested in learning more about Podsie, please visit www.podsie.org. You can also stay up-to-date with what Podsie’s doing by following them on Instagram, Twitter, or Linkedin.

Quick math time! What’s -2 - 4?

As a first-year teacher, that was a question most of my eighth-grade students struggled with during the first week of school. We spent a full week going over various strategies to help with negative integer operations, until finally, the concept clicked for them!

Then, because we had a massive amount of content to get through for the year, we put that topic aside and moved on. A few months later, we got to the solving equations unit, and it was time to put some of that old negative integers knowledge to use on solving problems like:

x + 4 = -2

To my dismay, the majority of my students had forgotten how to do negative integer operations, and it took another full day of review before they felt comfortable with it again.

The next school year, I made some adjustments. This time, before we started our equations unit, I gave my classes some time to review the notes that we had taken on integer operations. Then, we spent another 10 minutes going through those notes together and doing whole class call and responses like this:

Me: “A negative minus a positive...”

Students: “Is like a negative plus a negative!”

What’s wrong with this picture?

Let’s take a step back and play the “what’s wrong with this picture?” game. However, rather than looking at pictures, we’ll examine my first two years of teaching to see what I could have done better from a learning science point of view.

Spaced practice

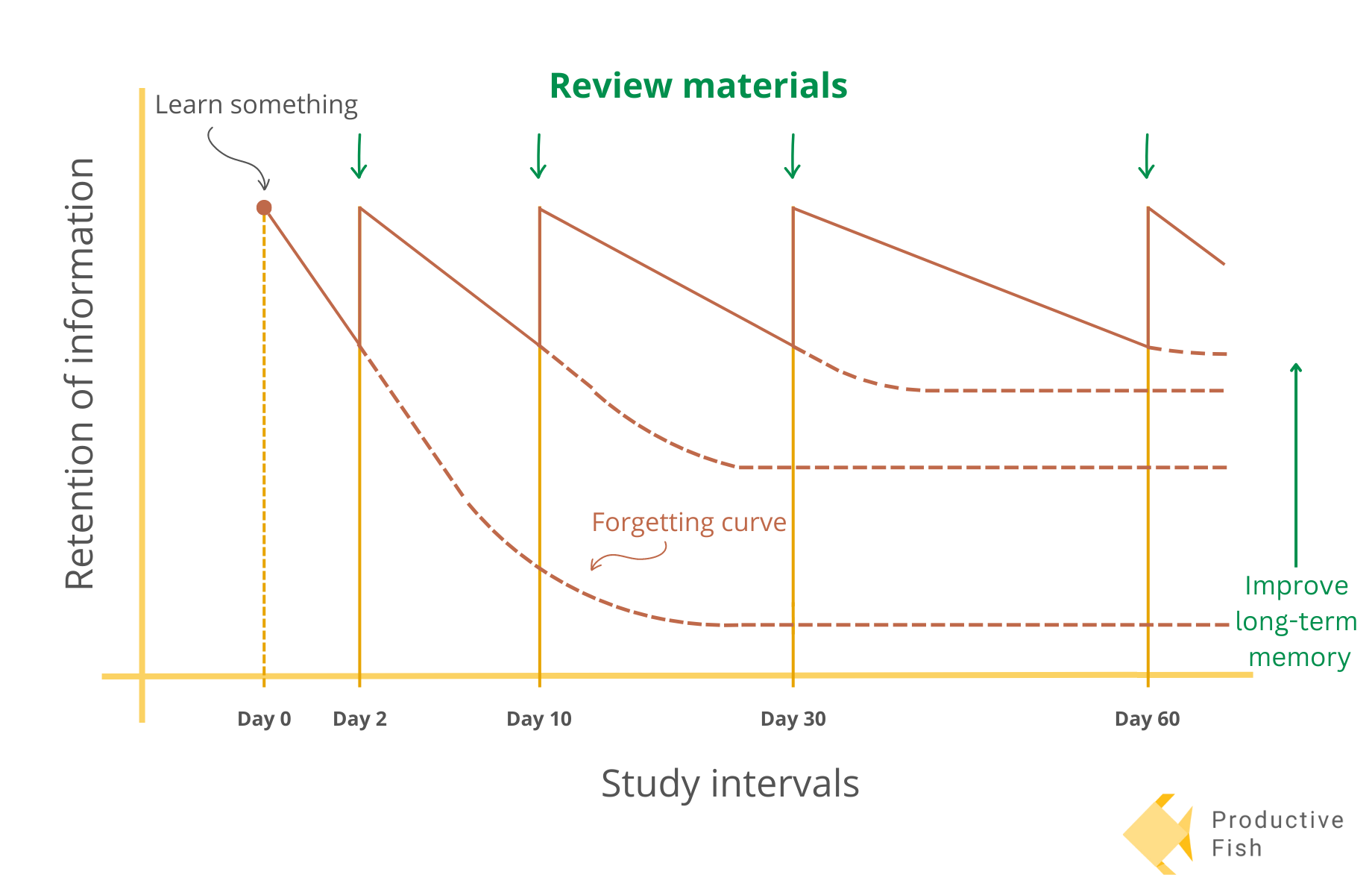

To ensure that my students still felt comfortable with negative integers by the time we got to the solving equations unit, I should have spaced out review opportunities in the months after they first learned that concept. The benefits of spaced practice have been well-documented throughout cognitive science research literature (1) and on The Learning Scientists Blog, but I think the case for spacing here is best highlighted by looking at a forgetting curve:

Image from Productive.Fish, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Forgetting curves generally show how, without review, a student can forget up to 60% of a topic just one day after learning it.

Like Doug Lemov, author of Teach Like a Champion, describes, the forgetting curve is an “imperfect” but “useful” tool (originally developed by a psychologist named Herman Ebingghaus in 1885 (2)) that helps us understand just how fast humans forget without review. In my case, asking my students to recall content that they hadn’t seen in months was simply setting them up for failure.

Retrieval

I could have also improved on the way I reviewed with my students. In my second year, I intuitively knew that my students needed more review, but instead of asking them to re-read notes or do whole class call-and-response, it would have been much more effective for them to engage in retrieval practice, another well-documented learning science strategy (3).

Concretely, this might have looked like providing them with some low-stakes practice on solving those negative integer operations, asking them to retrieve that knowledge from memory, and then providing feedback along the way to fill in any gaps or clarify misconceptions.

The bigger problem

If we dig deeper, the bigger problem was that as a teacher, I was not equipped with a concrete and thorough understanding of how people learn. In fact, I didn’t come across these cognitive science principles until a few years after I had left the classroom, when I read the book “Make It Stick” by Peter Brown, Henry Roediger, and Mark McDaniel.

Like it was for so many other educators, this book was hugely influential for me. On one hand, it formalized best practices that I had vague intuitions around and presented them in an evidence-based and definitive way.

More importantly, it revealed to me a clear gap between what learning science experts recommended and what was actually being implemented in classrooms.

Bridging the gap

At Podsie, we’re trying to help bridge that gap. Podsie is a nonprofit organization committed to empowering teachers and improving student learning by ensuring that all teachers and students have access to learning science best practices.

We want to do this in a couple of ways. First, we want to join in the movement of educators, researchers, and educational leaders who have already been working tirelessly towards this goal. We want to form partnerships, share what they’ve already been doing, and help create more resources that teachers and students can use.

Podsie the web tool

One of the key resources we’ve created so far is Podsie the web tool, which allows teachers and students to more easily implement spacing and retrieval in their classrooms.

To provide a brief overview of how this tool works, let’s imagine we were using Podsie back in my classroom. When my students first learned about negative integer operations, Podsie would have allowed me to give a formative assessment made up of questions that looked like this:

Short answer problem that asks students “What is -2 + 4?” Image provided by Joshua Ling.

Then, each question from that formative assessment would be inserted into each student’s Personal Deck, which is a deck that holds all of the questions that a student has been quizzed on so far in that class. We think of the Personal Deck as a representation of the entire body of knowledge that a student should know in a class throughout the school year:

The Personal Deck prompts students to review questions right when they are most likely to forget a concept. The review experience is personalized to each student. Image provided by Joshua Ling.

Each student’s Personal Deck maps each of the questions in the deck to a forgetting curve (similar to the one displayed above), and it prompts a student to review a question when it predicts that a student is about to forget that concept.

For example, if Jesse recently struggled with adding negative integers, while Ingrid recently struggled with multiplying negative integers, then Jesse’s Personal Deck will prompt him to review questions on adding, while Ingrid’s would prompt her to review questions on multiplying. Or, if Jesse previously did well on dividing negative integers, but hadn’t reviewed that concept in a week, then it would prompt him to review those dividing questions again.

Podsie also aims to provide meaningful retrieval practice. One issue we originally ran into when we first launched was students memorizing without understanding. For example, in the case of the -2 + 4 problem in the image above, during a Personal Deck review session, a student might have simply memorized that the correct answer is “2” without actually understanding how to add a negative integer. As a result, we recently added a feature that allows teachers to configure several question variations for a concept so that when the concept comes up in the student’s Personal Deck again for review, one of any of the variations might show up:

When reviewing questions in the Personal Deck, teachers can provide several variations of a question in order to promote meaningful retrieval. In this case, instead of allowing students to memorize that the answer to -2 + 4, a teacher challenges students to truly understand the concept of adding a negative integer by providing several variations (eg. -12 + 4, -4 + -4) that will show up during the Personal Deck review sessions. Image provided by Joshua Ling.

Overall, we want to continuously improve our web tool and build features that meaningfully improve student learning. Our goal is to make it easy for teachers and students to utilize spaced retrieval practice in a personalized way, so that they can review in an effective and targeted manner throughout the school year.

Looking Ahead

We launched a beta release of our web tool back in August of 2020, and since then, we’ve worked closely with 20 teachers and around 800 students to ensure that Podsie works well in the classroom. We’re excited to make Podsie freely available to all educators in June of 2021! During this first iteration, Podsie is geared more towards middle and high school classrooms, but it’s suitable for all subjects.

We hope that our web tool can make it easier for teachers and students to both utilize and learn more about learning science best practices. If you’re interested in getting access as soon as Podsie is publicly available, you can sign up today on the form at the bottom of www.podsie.org!

References:

(1) Kang, S. H. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: Policy implications for instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12-19.

(2) Ebbinghaus, H. E. (1964). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York, NY: Dover. (Original work published 1885).

(3) Roediger, H. L., Putnam, A. L., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational practice. In J. Mestre & B. Ross (Eds.), Psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education (pp. 1-36). Oxford: Elsevier.