How Do You Like Them Apples? On the Importance of Teaching in the Time of AI

Cover image by Michal Jarmoluk from Pixabay

By Althea Need Kaminske

I have a clear memory of sitting at the kitchen table in the early 2000s talking to my dad about this new thing: Google. My dad was a sci-fi and tech geek. We always had a copy of WIRED magazine in the house and technology was a frequent topic of discussion. In this particular conversation I had a question about something (I forget what now) and my dad excitedly proclaimed, "Let's look it up!". We got out of our seats in the kitchen, went to the living room, and crowded around the computer to look it up. What incredible power! What would it be like for me to come of age during a time when we have such unrestricted access to the world's knowledge? What would it be like to grow up in the information age??

I think of those conversations with my dad often. About the enthusiasm and curiosity they inspired in me. And the stark contrast in how I felt about technology and the future then to how I feel about technology and the future now. All of which was highlighted for me recently when I tapped my phone - my little doom machine - awake to send a message, only to receive a Google News recommendation about an article in Forbes magazine entitled, “When Knowledge is Free, What are Professors For?”. The article clarifies, "For decades, universities have operated on a bundled model: combining information delivery, skill development, credentialing, and social networking into a premium package. AI is now attacking the most profitable part of that bundle—information transfer—while employers increasingly value what machines cannot replicate: human judgment under uncertainty.” If this was an isolated article I might have passed it over as an oddity, a misguided piece of rage bait designed to be provocative for engagement. Unfortunately, I work for a university that is gleefully promoting AI every chance they get, while shutting down academic programs, and refusing to print the student paper that happened to feature articles about a documentary critical of the university and how data centers, driven by AI, are harming the environment. All this just within the last few months. So, when my little doom machine sent me this Forbes article I saw it more of a logical extension of what I’ve been seeing in my own university, rather than an isolated take on ed tech.

"Bar scene," Gus Van Sant, Good Will Hunting, 1997.

Around the same time my dad and I were talking about Google at the kitchen table, I would have watched the bar scene from the 1997 film, Good Will Hunting, which gives one answer to the question, “When Knowledge is Free, What are Professors For?”. For those who are not familiar I highly recommend looking up a clip of the bar scene. Matt Damon's character - as the genius kid from working class South Boston, Will Hunting - puts down the snobby ponytail guy from Harvard by consistently one-upping ponytail's knowledge of economic theories. He ends his critical attack on ponytail by telling him that he "dropped a hundred and fifty grand" on an education he could have gotten "for a dollar fifty in late charges at the Public Library."

As it turns out most industrialized nations have been making knowledge free to access for some time as a matter of civic pride. It’s called the Public Library. If all you needed for knowledge was access then public libraries would have meant the downfall of education. If all you needed for knowledge was "information transfer" then Google would have put universities out of business. If you think AI can, in any meaningful way, replace communities of learning, then you fundamentally misunderstand what learning and teaching are.

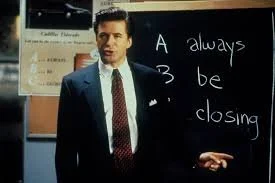

There have, of course, already been attempts to replace teachers with AI. WIRED magazine (after my dad passed I got my own subscription) recently published a piece on Alpha School’s promise to maximize learning through AI optimization without teachers. On paper, the school is a success - at least according to Alpha School. The article features interviews with former parents and students at the school that paint a bleak picture about what learning is like when it is completely driven by performance goals and algorithms. Students, driven to meet performance goals and get rewards, became distressed and withheld food from themselves to push themselves to meet goals. One thirteen year old said, “I think at one point I didn’t eat for most of the day because I told myself I don’t eat unless I get something right. I have to do this. Rewards, rewards, motivation, everything became a reward.” We usually only present scientific articles in this blog, so I’ll provide the disclaimer that these are anecdotal reports. Alpha School’s sole reliance on algorithmic learning is an extreme example of how AI might be adopted into the classroom. It is, however, a real world example that provides a case study in what can happen when you encourage school-age kids to approach learning like they’re making sales quotas (I’ve never watched the 1992 film Glengarry Glen Ross, but I know that “Coffee is for closers”).

“Coffee is for Closers Scene”, James Foley, Glengarry Glen Ross, 1992.

Before my little doom machine distracted me, I was going to write this blog post about deliberate practice and expertise development. About the importance of teachers (experts) in helping learners (novices) in developing metacognitive awareness through deliberate practice (1). About how becoming an expert is about more than just knowing more. About how becoming an expert is about knowing different (2). Experts don’t just know more than novices, they think about problems differently. For example, expert physicians have richer networks of association about diseases, allowing them to see more connections among diseases and consider more options when making a diagnosis compared to novices (3, 4).

I was going to write about how thinking is hard (5) - but we do it anyways. That thinking critically about something is just about knowing more stuff, but about caring enough to think through the problem (6). Caring enough about a problem to talk about it with others. Caring enough to be wrong because the answers to your questions are worth more than your ego.

I was going to write more about how expertise is not just a cognitive process, allowing experts to process information more quickly (7, 8, 9). About how being an expert is also a social process where you become a part of a community of other experts who can hold you accountable to community standards (10).

Whatever teaching and learning are, they are more than my attempts to explain them with terms like “expertise development” and “metacognitive awareness”. They are more than “information transfer”, as if knowledge were funds in a bank that you can transfer from one account to another. I was going to tell you about the fascinating intricacies and nuances that underlie the transformative process of learning and teaching, but now all I want to tell you is that what you do every day as a teacher and as a learner is transformative, not transactive.

Teachers don’t just know more things than their students. They help to guide students through the learning process - providing feedback, setting expectations, and suggesting alternate strategies for learners (1). They also meet students where they’re at, with knowledge of what is developmentally appropriate for learners of different ages, abilities, and backgrounds (11, 12, 13). In short, teachers have the profound ability to treat students as people. People who have things that affect them outside of the classroom. People who have hopes and dreams for the future. People who have interests and a sense of humor. People who are worth more than the sum of their scores on tests. People who are far more complex than any single algorithm can predict.

“Will and Sean”, Gus Van Sant, Good Will Hunting, 1997.

While Will Hunting was able to access knowledge from the public library and forgo university, he was also the exception that proved the rule. None of his other friends, who had the same access as he did, were able to achieve his level of genius. Further, even though he was clearly smart, without guidance from a mentor and community he was unable to use that knowledge effectively. It’s not until he goes to therapy and gets mentorship from Sean that he’s able to do anything productive with all that genius. Even Will Hunting needed a teacher. The ultimate growth in the film wasn’t about becoming smarter or richer - it was about gaining the emotional maturity to pursue a meaningful relationship.

My dad used to wonder what it would be like for me to grow up in the information age. What could I accomplish with all the world’s information at my disposal? I’m sure that it has helped me in ways I’ll never be able to quantify. As I look at my phone, my little doom machine, never more than an arm’s length away, I am sure that it has harmed me in ways that I’ll never be able to quantify either. When I think about what learning experiences I’ve had that have been transformative, I think about my English teachers who helped me to feel I was part of a grand tradition of learning, a cannon that I could use as a touch point to talk to other people in my community. I think a lot about the Thought and Knowledge class I took as part of the IB program, and how that was my first introduction to philosophy and served as a foundation when I went to university. I think about working in research labs at university, and the sense of community we had and the celebrations around thinking. Weekly lab meetings weren’t dry progress reports, they were community building events with inside jokes, shared meals, and words of encouragement and support from other members. Thinking is hard, but I had a whole community to celebrate and support me thanks to my teachers. Now I wonder what it will be like for my child to grow up in the post-information age where the machines will do the thinking for you so it’s not as hard. I don’t know what it will be like for him, but I hope he has some really good teachers.

References

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Romer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 361–406. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.190327

Bédard, J., & M. T.H. Chi (1992). Expertise. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(4), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10769799

Feltovich, P. J., Johnson, P. E., Moller, J. H., & Swanson, D. B. (1984). LCS: The role and development of medical knowledge in diagnostic expertise. In W. J. Clancey & E. H. Shortliffe (Eds.), Readings in medical artificial intelligence (pp. 275–319).

Heller, R., Saltzein, H. D., & Caspe, W. (1992). Heuristics in medical and non-medical decision making. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: A: Human Experimental Psychology, 44(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/02724989243000019

David, L., Vassena, E., & Bijleveld, E. (2024). The unpleasantness of thinking: A meta-analytic review of the association between mental effort and negative affect, Psychological Bulletin, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000443

Halpern, D. F. (2014). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking (5th ed.). Psychology PressChase, W., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4, 55–81.

Chase, W., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess. Cognitive Psychology, 4, 55–81.

Hatano, G., & Osawa, K. (1983). Digit memory of grand experts in abacus-derived mental calculation. Cognition, 15(1–3), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(83)90035-5

Ericsson, K. A., & Kintsch, W. (1995). Long-term working memory. Psychological Review, 102(2), 211–245. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.211

Imundo, M. N., Watanabe, M., Potter, A. H., Gong, J., Arner, T., & McNamara, D. S. (2024). Expert Thinking with Generative Chatbots. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 13(4), 465-484. https://doi.org/10.1037/mac0000199

Susana H. Hernández, Lyle McKinney, Andrea Burridge, & Catherine O’Brien. (2024). Validating Classrooms: Teaching Strategies to Advance Equity in Developmental Education. AERA Open, 10(1).

Barhoum, S. (2018). Increasing Student Success: Structural Recommendations for Community Colleges. Journal of Developmental Education, 41(3), 18–25.

Cox, R. D. (2009). “It Was Just that I Was Afraid”: Promoting Success by Addressing Students’ Fear of Failure. Community College Review, 37(1), 52–80. https://doi-org.proxy.ulib.uits.iu.edu/10.1177/0091552109338390