Mary Whiton Calkins

by Althea Need Kaminske

(cover image from public domain)

In the past month I’ve been thinking a lot about history. I was tasked with writing a brief overview of cognitive psychology for a book I’m writing with Megan, and someone wrote into the Learning Scientists interested in the history of learning and asking for some places to start. I was not prepared for either of these requests. I never had the chance to take a class on the history of psychology, so the only history I knew was more or less what was presented in the textbooks I used for class. These all tend to paint a similar, unidimensional picture of the history of cognitive psychology which I would summarize as: Important men (mostly white and European) had important ideas. Then the computer came along! This changed some of these ideas. And then the men (mostly white and American, but now with some women) continued to have important ideas that you’ll learn more about in this book. These histories are often related as a series of dates with little mention of the lives and circumstances of the players involved; flattening otherwise dynamic, charismatic, and flawed (i.e. human) people into figureheads and symbols for schools of thought*. This paints a rather flat and unsatisfying picture.

After some initial digging, I can report back that the history of learning is much broader than just the history of cognitive psychology. Even the history of cognitive psychology is broader than cognitive psychology - encompassing the various disciplines that make up Cognitive Science (philosophy, neuroscience, computer science, linguistics, anthropology, and psychology), and at a pivotal point in its development spanning two world wars†. As the Ebbinghaus quote says, “Psychology has a long past, but a short history” (1).

All of this is to say that even if you have a degree in Psychology the only thing you probably know about Mary Whiton Calkins is that she was the first female president of the American Psychological Association. She was also, separately, the first female president of the American Philosophical Association. I was also delighted to find out that her early work focused on memory. Her ideas and theories about paired associate learning and the effects of primacy and recency predated modern memory research by about 70 years. She also was never awarded her PhD.

Mary Whiton Calkins was born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1863. She was the oldest of five children. She spent her childhood in Buffalo, New York, then moved with her family to Newton, Massachusetts in 1881. Calkins went to Smith College to study philosophy and the classics - during a time when it was uncommon for women to pursue higher education. After completing her undergraduate degree, and traveling Europe for a year with her family, Calkins was offered a job at Wellesley College teaching Greek (2).

Her skill in teaching and interest in philosophy prompted her department to recommend that Calkins be appointed to the newly created position in experimental psychology. The college agreed on the stipulation that she take some time off to study the subject further. This required special arrangements since the nearby universities offering courses in psychology did not take women. So Calkins was independently tutored by Edmund Sanford of Clark University and attended seminars from William James of Harvard University.

“I have been attacking the President again on the subject you know of. He tells me that the overseers are so sensitive on the subject that he dares take no liberties. … They are at present in hot water about it at the medical school he himself being for the admission of women.” William James, 1890 (3)

A brief aside for those who are unfamiliar with William James. He is credited with being the “Father of American Psychology”. He was also a philosopher and credited with establishing pragmatism in philosophy‡. His brother was Henry James, celebrated American novelist, and his sister was Alice James, noted diarist. Unlike many early figures in psychology he disliked conducting research and instead focused on teaching and writing. By my count he published over 300 works in his lifetime (I counted the number of items in the 47 pages of bibliography in the back of The Writings of William James (4). There may be some duplicates in this count, but not many. It’s a truly impressive amount of writing.). In psychology his most famous work is two volumes entitled Principles of Psychology which are remarkable in their descriptions of various psychological phenomena and are eminently quotable even now, some 130 years later.

“I began the serious study of psychology with William James. Most unhappily for them and most fortunately for me the other members of his seminary in psychology dropped away in the early weeks of the fall of 1890; and James and I were left … quite literally at either side of a library fire. The Principles of Psychology was warm from the press; and my absorbed study of those brilliant, erudite, and provocative volumes, as interpreted by their writer, was my introduction to psychology.” Mary Whiton Calkins, 1930 (5, p. 31)

When Calkins returned to Wellesley in 1891 she established a psychological laboratory and introduced experimental psychology into the curriculum. At the time there were only a dozen or so other psychological laboratories in North America. In the first year students dissected sheep’s brains and conducted experiments on sensation, association, space, perception, memory, and reaction time (2). She was invited by G. Stanley Hall❡ to publish an article describing her experimental psychology course in the American Journal of Psychology. Calkins published a series of reports on findings from her and her students in the lab over the next 10 years (2).

After establishing her laboratory, Calkins returned to Harvard to work in the laboratory of Hugo Münsterberg§ . Here, Calkins pioneered the use of paired-associate learning, a methodology that is heavily used in memory research today. Her method involved showing a series of colors paired with numbers, then testing the memory of the numbers when shown the colors. She demonstrated that while numbers were remembered better when paired with bright colors, it was the frequency of the exposure that mattered for memory (7, 8, 9).

“She was one of the first in this new field, and she created an experimental technique that is now called the method of paired-associates, which has survived to the present time.” Hernstein & Boring, 1966 (10)

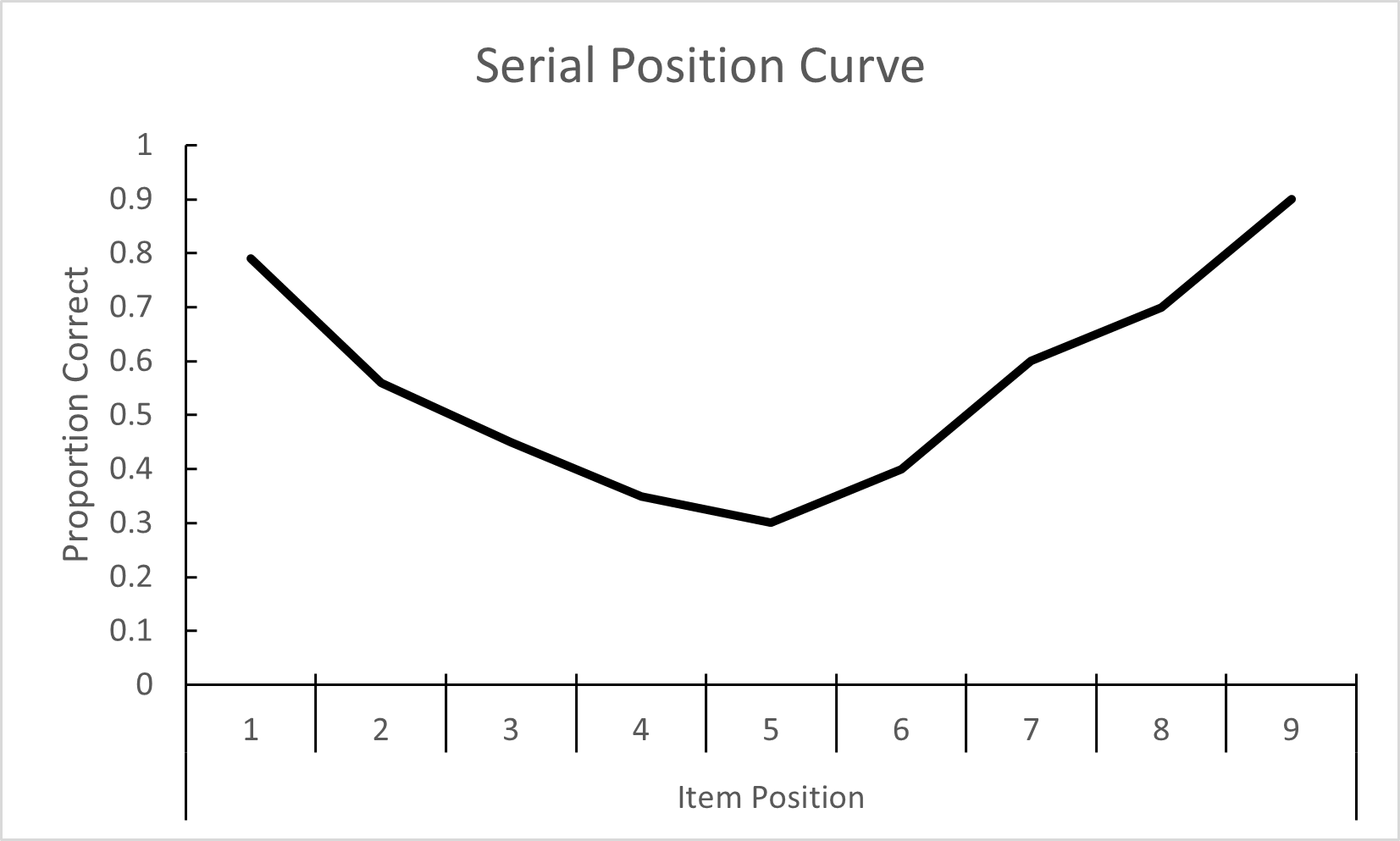

Calkins made several notable observations that are of interest to modern memory researchers (11), but before I go on to describe some of her observations it will be useful for you to know about the Serial Position Curve. If I were to read you a list of items - say I’m cooking a new dish and ask you to get a list of ingredients at the store - you would likely repeat those items back to me in a predictable pattern. People tend to remember the first items on the list really well, remember less and less as the list goes on, and then remember the last item or two on the list really well again. We call this the serial-position effect, or serial position curve.

Example of a Serial Position Curve. Items at the beginning and the end of the list are more likely to be recalled than items in the middle of the list, creating a U-shaped function.

In the first part of the Serial Position Curve we see a memory advantage for items that were presented first, an effect we call the primacy effect.

That last part, where performance improves for the last few items, is what memory researchers call the recency effect. Essentially, you know that you are going to forget the last few items if you go back to the beginning of the list and recall them all in order, so you dump the last few items from short term memory before going back and trying to recall the whole thing.

Some of Calkin’s early observations included:

Recency. Calkins was aware that recency could affect how people remembered her stimuli, so she was careful to arrange test sequences so that the last pair that was presented in a list was not the first to be tested, “so that no after-image of the numeral might remain” (9). In an unscientific sampling of the three cognitive psychology and memory textbooks that I have at my desk Murdock (1962) is the most commonly cited paper describing this phenomenon and none mention Calkins. Murdock’s paper is titled “The Serial Position Effect of Free Recall” so it makes sense that this is what is most commonly cited (12), but I point this out to explain my surprise at discovering that Calkins was describing these phenomena back in 1896.

Modality Effects. Calkins conducted two sets of experiments, one set using visual presentation, the other using auditory presentations. She noted that both sets were similar, except that the recency effects were stronger in the auditory presentations (11).

Negative Recency Effect. The recency effect, as described above, goes away when there is a delay. Your memory for those items quickly fades and you aren’t able to apply the same processes, or at least not to the same degree, as you were with the other items on the list. “This decrease is evidently the result of fatigue; the twelfth pair is not observed with the same attention as the earlier ones” (7).

Primacy Effects. Calkins stated in 1896, that the subject “may not only accentuate the first presentation but recur to it while learning the rest of the series” (9). Rundus (1971) and Glanzer (1972) concluded some 80 years later that the primacy effect occurs because we tend to rehearse the first item as we are going through the list (again these are the citations most commonly given in my textbooks) (13, 14). She was also possibly the first person to use the term primacy when talking about recall experiments (11).

Calkins’ memory research in Münsterberg’s lab was rigorous and ground breaking. She was granted an oral defense of her work in 1895 and her committee - comprised of William James, Hugo Münsterberg, Josiah Royce, George Santayana, and others∥ - unanimously agreed that her work was meritorious enough to earn a Ph.D. (6). She was denied on the basis that she was never officially a student.

A picture of Mary Whiton calkins wearing academic regalia. Public domain

In 1902 Radcliffe, Harvard’s affiliated women’s college offered Calkins, along with three other women, graduate degrees from Radcliffe. Calkins politely declined (6). In 1927 there was a petition to Harvard to award Calkins her Ph.D. The petition included prominent psychologists, and Harvard alumni, R. M. Yerkes, E. L. Thorndike, and R. S. Woodworth#. It was denied (15). In 2002, psychologist Karyn Boatwright and her students at Kalamazoo College created a website (unfortunately now defunct) Justice for Mary Whiton Calkins to garner support to award her Ph.D. The petition was denied and archived in 2016. There is currently a petition on change.org to award Mary Whiton Calkins her PhD.

Calkins research shifted away from memory research and pursued more theoretical and philosophical areas of scholarship, notably developing her system of self-psychology. She viewed classic experimental psychology “as out of touch - as deliberately and on principle out of touch - with important portions and aspects of that subject matter as it presents itself in ordinary experience.” (16).

In 1903 James McKeen Cattell** asked ten prominent psychologists to rank their American colleagues in respect to the importance of their work, and Calkins was ranked 12th out of 50 (2). In 1905 she was elected as president of the American Psychological Association. In 1918 she was elected as president of the American Philosophical Association. She received honorary degrees from Columbia University and her alma mater, Smith. She was the first woman elected to honorary membership in the British Psychological Association in 1928.

Why isn’t Calkins’ research more well known and credited? There are, of course, a variety of reasons. In addition to issues of structural sexism, there are few historical quirks in cognitive psychology that contributed. First, the study of memory and the methods used to study memory fell out of mainstream psychology during the first part of the 20th century as Behaviorism became mainstream. Second, Calkin’s was not mentioned in connection with paired associate learning in E. G. Boring’s influential A History of Experimental Psychology (11, 19). One of the things that struck me about Calkin’s story is that even despite the high praise and advocacy from her male peers, she still was unable to get her Ph.D. and receives less recognition than her contemporary male peers today. For me, this highlights the importance of history in an area in order to understand why some ideas and theories receive attention while others don’t.

Footnotes

*Of course, these books are written this way in part due to the limitations of space and scope. Psychology is a large discipline, it makes sense to paint in broad strokes to get the gist across. There are academic journals on the history of psychology, history textbooks, and even history of psychology courses that go into far more detail. Nonetheless, most people who are familiar with psychology likely have only taken an Intro Psych course and, like me, are really only familiar with this abbreviated history.

†Military history fun fact: Despite successful demonstrations, the military ultimately terminated psychologist B. F. Skinner’s Project Orcon which trained pigeons to guide missiles.

‡Experimental psychology as its own separate discipline is given the official start date of 1879 when Wilhelm Wundt established the first psychology laboratory in Germany. Both he and William James fit the mold of early psychological researchers - physiologist-philosophers. Several early psychologists were practicing physicians AND philosophers. You could do it all in the 19th century! William James, however, abandoned medicine shortly after earning his MD from Harvard in 1869 and never practiced medicine.

❡Another notable figure in early Psychology, having earned the first official doctorate in psychology in the United States, starting the first journal dedicated to psychology in the United States, American Journal of Psychology, and the first president of the American Psychological Association. If you’re a psychologist you probably made an appreciative “hm” when you read his name. A lot of Calkins’ biography is a long list of the most respected names in the discipline showering her with praise.

§Another important figure in early psychology, Münsterberg was a student of Wilhelm Wundt who was recruited by William James to start the first psychology laboratory at Harvard since James had no desire to conduct research. In Principles of Psychology, James referred to Münsterberg’s work as “beautiful examples of experiments on reaction-time” and “masterly experiments on time perception.” (6) However, unlike some of the other important names mentioned here Münsterberg is somewhat obscure. Originally from Germany, Münsterberg was disheartened by how his country was depicted in the media leading up to WWI and wrote several pieces trying to inform public sentiment. This led to perhaps the only time in history when a department chair has asked their faculty to publish less (6).

∥Psychology and Philosophy were in the same department at this point in Harvard. So her committee is a list of very prominent psychologists and philosophers.

#Again, this is a very impressive list of names. You might be familiar with the Yerkes-Dodson law (i.e. the performance-arousal curve), or Thorndike’s puzzle boxes and law of effect.

**First professor of psychology in the United States. He studied under Wundt and did much to advance psychology as a science. He also had some problematic views on eugenics (in that he was pro). Even less well known is that while consuming hashish while studying the effect of drugs at Harvard, he wrote what he felt to be a verse more beautiful than Shelly’s. The verse turned out to be: In the Spring/The Birds sing (6). Also of note is that his daughter, Psyche Cattell’s, work is often misattributed to him (6).

References

Ebbinghaus, H. (1908). Psychology: An elementary text-book. (M. Meyer, Trans.). D C Heath & Co Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1037/13638-000

Furumoto, L. (1990). Mary Whiton Calkins (1863-1930). In O’Connel, A. N. & Russo, N. F. (Eds.). Women in psychology: A bio-bibliographic sourcebook (pp.57-74). Greenwood Press: West Port, Connecticut.

Benjamin, L. T., Jr. (2006). A History of Psychology in Letters (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing.

McDermott, J. J. (1967). The Writings of William James. Random House, Inc.

Calkins, M. W. (1930). Mary Whiton Calkins. In C. Murichison (ed.), History of psychology in autobiography, (vol. 1, pp. 31-36). Worcester, MA: Clark University Press.

Hothersall, D. & Lovett, B. J. (2022). History of Psychology (5th ed.). Cambridge University Press: New York, USA.

Calkins, M. W. (1894). Association (I.) Psychological Review, 1, 476-483.

Calkins, M. W. (1896a). Association (II.). Psychological Review, 3(1), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0068098

Calkins, M. W. (1896b). Association: An essay analytical and experimental. Psychological Review Monograph Supplements, 1 (2).

Hernnsetein, R. J. & Boring, E. G. (Eds.). (1966). A source book in the history of psychology. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Madigan, S. & O’Hara, R. (1992). Short-term memory at the turn of the century: Mary Whiton Calkin’s Memory Research. American Psychologist, 47(2), 170-174.

Murdock, B. B., Jr. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(5), 482-488.

Rundus, D. (1971). Analysis of rehearsal processes in free recall. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 89, 63-77.

Glanzer, M. (1972). Storage mechanisms in free recall. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 5, pp. 129-193.). San Diego, CA: Academic press.

Young, J. L. (2010). Profile of Mary Whiton Calkins. In A. Rutherford (Ed.), Psychology's Feminist Voices Digital Archive. Retrieved from https://feministvoices.com/profiles/mary-whiton-calkins/

Heidbreder, E. (1972). Mary Whiton Calkins: A discussion. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 8, 56-68.

Boring, E. G. (1950). A History of Experimental Psychology (2nd ed.). Appleton-Century-Crofts